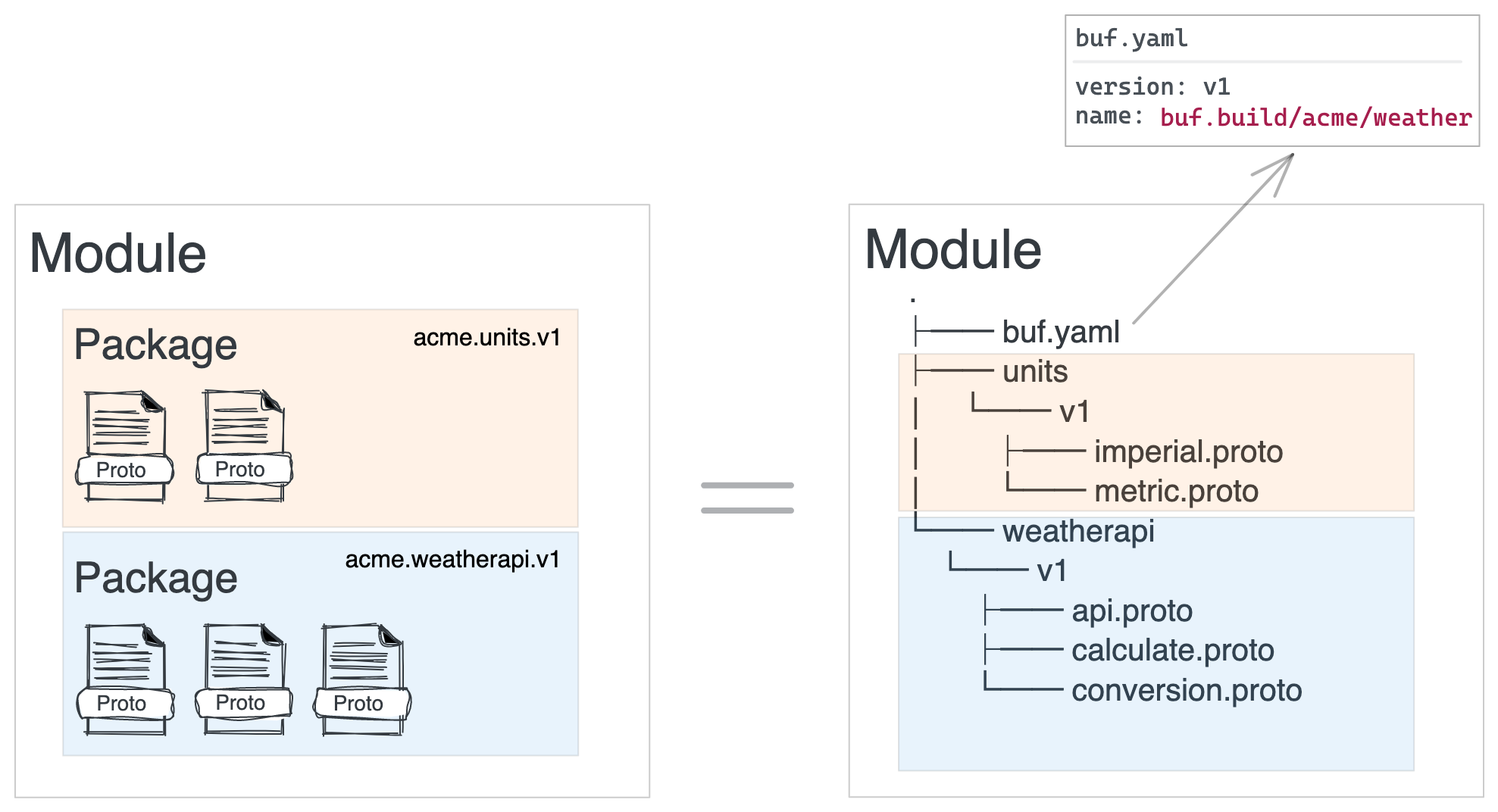

A module is a collection of Protobuf files that are configured, built, and

versioned as a logical unit. By moving away from individual .proto files, the

module simplifies file discovery and eliminates the need for complex build

scripts to -I include, exclude, and configure your Protobuf sources.

Storing modules in the BSR, a Protobuf-aware registry, protects you from publishing broken builds. Module consumers have confidence that the modules that they pull compile, something that isn't possible with traditional version control systems.

The module's name uniquely identifies and gives ownership to a collection of Protobuf files, which means you can push modules to authorized repositories within the BSR, add hosted modules as dependencies, consume modules as part of code generation, and much more.

A module is identified by a name key in the

buf.yaml file, which is placed at the root

of the Protobuf source files it defines. This tells buf where to search for

.proto files, and how to handle imports. Unlike protoc, where you manually

specify .proto files, buf recursively discovers all .proto files under

configuration to build the module.

version: v1

name: buf.build/acme/weather

The module name is composed of three parts: the remote, owner, and repository:

- Remote: The DNS name for the server hosting the BSR. This is always

buf.build. - Owner: An entity that is either a user or organization within the BSR ecosystem.

- Repository: Stores all versions of a single module

Create a module

To create a Buf module, you should start by collecting one or more related Protobuf packages within a module, each serving a specific and valuable function. For instance, you can create a module consisting of packages with APIs for financial analysis to enable other developers building financial applications to use your work.

The Protobuf language organizes packages, and packages group into buf modules. Your module declares dependencies required to run your code, including the set of other modules it needs.

As you add new features or improve the functionality of your module, you can release updated versions. This allows developers using your module to import the most recent packages and test them before deploying them to production. They can make RPC calls to your module and experiment with the new version, making sure it meets their requirements before using it in production.

-

Open a command prompt and

cdto your projects root directory. Create aprotodirectory for your buf module source code.$ mkdir proto $ cd proto -

Start your module using the buf mod init command.

Run the

buf mod initcommand, giving it your module path -- here, usebuf.build/acme/greet. If you publish a module, this must be a path from which your module can be downloaded bybuf. That would be your code's repository on the Buf Schema Registry. For more on naming your module, see Managing dependencies.$ buf mod init buf.build/acme/greetThe

buf mod initcommand creates abuf.yamlfile to track your code's dependencies. So far, the file includes only the name of your module and the version. But as you add dependencies, the buf.yaml file will list the versions your code depends on. This keeps builds reproducible and gives you direct control over which module versions to use. -

In your text editor, create a file in which to write your code and call it

greet/v1/greet.proto.$ mkdir -p greet/v1 $ touch greet/v1/greet.proto -

Paste the following code into your

greet/v1/greet.protofile and save the file.syntax = "proto3"; package greet.v1; message GreetRequest { string name = 1; } message GreetResponse { string greeting = 1; } service GreetService { rpc Greet(GreetRequest) returns (GreetResponse) {} }This is the first code for your module. It returns a greeting to any caller that asks for one.

That's it! You've created a Buf module with a single Protobuf package. Next, learn how to publish a module

Source Management

While the Buf Schema Registry (BSR) automatically enforces module compilation upon pushing, there are additional best practices that are worth considering during module development. In this context, we'll discuss these best practices and explain their importance.

Organizing code in the repository

By adhering to the conventions outlined in this guide, you can streamline maintenance and enhance the development experience for your module. Incorporating your module code into a repository is usually as straightforward as it is with other code. To further clarify, please refer to the diagram below, which demonstrates a source hierarchy for a simple module containing two packages.

proto/

├── acme

│ └── pkg

│ └── v1

│ └── pkg.proto

├── buf.lock

├── buf.md

├── buf.yaml

└── LICENSE

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| LICENSE | The module's license. |

| buf.md | The buf.md file is similar to the README.md file found in GitHub repositories, and it currently accommodates all the syntax provided by CommonMark. |

| buf.yaml | Describes the module, including its module path (which effectively serves as its name) and its dependencies. For additional information, please refer to the buf.yaml reference. The module name will be specified using a name directive, as shown in the following example: name: buf.build/bufbuild/eliza. For further guidance on selecting an appropriate module path, please consult the Managing Dependencies section. |

| buf.lock | This file includes the module's dependencies, which buf uses to manage the dependent modules and their versions. The file will be empty or non-existent if there are no dependencies. It's not recommended to manually modify this file, except when using the buf mod update command. |

Package directories and .proto sources. | Directories and .proto files that make up the Protobuf packages and sources within the module. |

Module layout

While the module is already a versioned entity composed of Protobuf files, it's advisable to implement some level of versioning in its directory and package structure as well.

For example, suppose you're creating the buf.build/acme/pkg module, which initially contains a single .proto file. In

that case, it's preferable to nest this file within a directory and define a unique package that differentiates it from

other module dependencies, rather than placing it at the root of the module (alongside the buf.yaml and buf.lock files).

| Bad | Good |

|---|---|

| |

Failing to adhere to this best practice increases the likelihood of API collisions with other user-defined APIs. For

instance, if a consumer intends to import Protobuf definitions from two modules that both define an api.proto file, the

resulting module won't compile. This is because the compiler can't differentiate between which api.proto file to

reference if there are multiple versions of it.

The module layout described here is included in the

MINIMALlint category.

Module Documentation

In addition to comments associated with your Protobuf definitions, it's necessary to have a way for module authors to describe the module's functionality for others to understand. To achieve this, you can create a buf.md file in the same directory as the module's buf.yaml file and push it to the BSR in the usual manner. As documentation is an integral part of the module, any changes made to the buf.md file result in new commits in the BSR.

The buf.md file is similar to a GitHub repository's README.md and currently supports all CommonMark syntax.

proto/

├── acme

│ └── pkg

│ └── v1

│ └── pkg.proto

├── buf.lock

├── buf.md

└── buf.yaml

Module License

Public repositories on the Buf Schema Registry are often used to share open source software. For your repository to truly be open source, you'll need to license it so that others are free to use, change, and distribute the software.

As a best practice, we encourage you to include the license file with your project. To do this, simply include

a LICENSE in the same directory as your module's buf.yaml file and push it to the BSR like normal.

Buf aims to provide users with open-source license information to help them make informed decisions. However, we are not legal experts and do not guarantee the accuracy of the information provided. We recommend consulting with a professional for any legal issues related to open-source licenses.

Referencing a module

A module has different versions. Each version includes any number of changes, and each change is identifiable by a unique commit, tag, or draft. The collective set of module versions is housed within a repository.

Commit: Every push of new content to a repository is associated with a commit that identifies that change in the schema. The commit is created after a successful push. This means that unlike Git, the commit only exists on the BSR repository and not locally.

Tag: A reference to a single commit but with a human-readable name, similar to a Git tag. It is useful for identifying commonly referenced commits—like a release.

Draft: A temporary commit in a development workflow with a human-readable

name, similar to a Git feature branch but without history. It is useful for

iterating on a module while keeping those changes outside the main branch. Can

be overwritten and deleted. When it

is used as a dependency in buf.yaml of a module, the module cannot be pushed

until you update to a non-draft commit of the dependency.

Local modules with workspaces

If you want to depend on local modules, you can set up a

workspace to discover modules through your file

system. If you are in a workspace, buf looks for deps in your

workspace configuration before

attempting to find it on the BSR.

This makes workspaces a good way to iterate on multiple modules at the same time before pushing any changes to the BSR.

Module cache

buf caches files it downloads as part of module resolution in a folder on the

local filesystem to avoid incurring the cost of downloading modules repeatedly.

To choose where to cache the files, it checks these, in order:

- The value of

$BUF_CACHE_DIR, if set. - The value of

$XDG_CACHE_HOMEfalling back to$HOME/.cacheon Linux and Mac and%LocalAppData%for Windows.